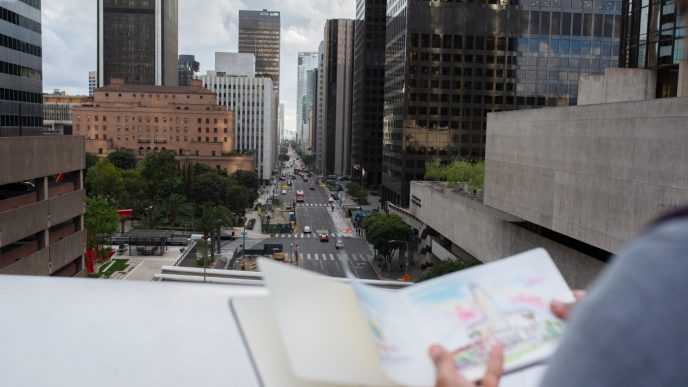

At border airports, where construction crews unload wind turbine components wearing safety jackets bearing foreign brands, you begin to notice it. Or in hotel lobbies, where European solar developers wait for final approvals while sipping strong coffee. These now-almost-routine instances reveal a larger narrative: capital is shifting in the direction of energy.

Energy financiers now find what was formerly thought to be a hazardous area to be incredibly alluring. Countries that global corporations have traditionally avoided are becoming the focus of important meetings and bids for billion-dollar projects. This scramble is similar to the first one in several aspects, but it involves more than just oil. It concerns all forms of electricity, including gas, hydro, solar, and even the minerals required to construct grids and batteries.

| Key Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Demand for Power | Rapid population growth and industrial expansion create urgent energy needs |

| Abundant Resources | Rich in sunlight, wind, oil, gas, and essential minerals like lithium |

| Capital and Technology Gap | Foreign funds and know-how fill the local infrastructure and skills void |

| High Return Potential | Greater risks offer larger profits than developed markets |

| Geopolitical Strategy | Countries invest abroad to gain influence and secure long-term interests |

| Policy Incentives | Governments offer tax breaks and streamlined regulations |

| Clean Energy Shift | Global momentum toward renewables boosts appeal of untapped regions |

The need for energy is growing, and this newfound interest has a very obvious cause. In countries like Bolivia, Bangladesh, and Uganda, cities are expanding more quickly than their electricity plants can handle. Fans, phone chargers, and refrigerators are now necessities for households that previously lacked electricity. Production lines are still halted by outages despite factories being bustling with activity. There is a vacuum as a result of the discrepancy between what is required and what is available, and investors detest vacuums. They fill them.

The majority of local systems lack the large funds and cutting-edge technology that come with foreign cash, which frequently arrives as joint ventures or strategic alliances. It can take the shape of smart grids, high-efficiency turbines, or storage options that can compensate for unpredictable supply. These investments are not only welcome but also crucial for many administrations. The necessary level of change cannot be covered by domestic funding alone.

For example, Nigeria’s grid was weak and unreliable due to decades of underinvestment. Global financiers are now supporting off-grid solar enterprises that completely eliminate the need for massive public grids. It’s a setting-specific economic model that’s quick, decentralized, and incredibly effective at reaching overdue communities.

However, this capital doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It is enticed. Governments have gotten especially skilled at crafting strategies to draw in investors in recent years. The strategy is becoming increasingly complex and includes things like secured power purchase agreements and tax advantages. To avoid the danger of inflation, some provide long-term contracts linked to hard currency. Others reduce the bureaucratic burden that once turned off investors by providing land access and expediting the permitting process.

However, not all motivations are solely financial. Nations like Saudi Arabia and China are investing for both reach and profit. Refineries and solar fields are examples of geopolitical imprints in addition to energy developments. They create partnerships, develop trade routes, and guarantee access to resources like lithium and cobalt, all of which are essential for the transition to renewable energy.

I heard a minister make the joke, “Everyone wants our sun and our soil,” while I was in Namibia last year. All we have to do is make sure we receive more than a handshake in exchange. It was an honest statement, but it was true. Too many impoverished areas have welcomed foreign investment for too long without reaping the long-term rewards. The abilities vanished, but the lights came on.

The long-term picture becomes complicated at this point. Building a power plant is not difficult. Increasing capacity is more difficult.

During a trade meeting in Accra, I saw one of the silent turning points. When a visiting investor wondered if local employees will ever manage the entire company rather than merely maintain the equipment, a young engineer got up to speak. The investor hesitated before responding. That silence conveyed a lot of information.

When it comes to rapidly constructing energy infrastructure, foreign cash can be extremely effective. However, it runs the risk of turning into a revolving door, which is advantageous in the short run but restrictive in the long run, if it excludes significant technology transfer or local training. Vietnam and other nations have demonstrated how to thread the needle. They have created a supply chain that is now globally competitive in addition to projects by requiring local content and rewarding knowledge sharing.

Financial models have also developed in recent years. More private capital has entered frontier energy markets thanks to blended finance, in which development banks lower investor risk. Green bonds are providing credibility and structure to renewable energy initiatives. Even crowdfunding approaches are assisting communities in co-owning energy solutions, albeit they are still specialized.

Meanwhile, developing energy markets present a particularly strong argument as international investors demand climate-aligned portfolios and ESG compliance. They enable organizations to fulfill impact and return goals. It’s an uncommon alignment, and the pressure for renewable energy is particularly strong because of it.

Notably, the dangers are still present even when the rewards are substantial. Confidence is still shaken by contract disputes, currency fluctuations, and political changes. A cabinet reshuffle or regulatory reversal might cause a contract that was struck with hope to fall apart. However, more and more investors and governments are building institutions that can outlast individual leaders in order to create safeguards.

Looking ahead, the speed of the investment is equally as impressive as its size. Negotiations that used to take years can now be completed in months. Timelines are being accelerated worldwide due to the urgency of energy demand and the momentum of climate targets.

How much local ownership and creativity are incorporated into these projects will be the true test. Will investors of today overlook ecosystems of talent, supply chains, and expertise in addition to infrastructure? The advantages could last for decades if they do.

If they don’t, the lights might turn on, but the future won’t be as bright as it should be.